From the book The Pontos of the Hellenes, the article below, written by Veroniki Dalakoura – Kamara doctor of Anthropogeography, Researcher, is posted here with the permission of the publishing company Ephesus.

My wish to study Hekklisia tis Trapezountos [The Church of Trebizond], the sole work that deals in detail with one of most important cities on the coast of the Pontos, led me to become acquainted with its writer, Metropolitan Chrysanthos of Trebizond (1913-1925) and Archbishop of Athens (1938-1941). It is difficult to convey in a few pages even the outline of a personality with the stature of Metropolitan Chrysanthos. I will therefore emphasize those points that highlight the course of a prelate who on the one hand played a significant role at a critical period in the history of the Pontic Greeks, and on the other was distinguished as an outstanding church scholar for his intellectual and spiritual contribution and his moral fiber.

Childhood and studies

“I don’t remember my father, I was very young when he died … and my sister Elisabeth… I remember her vividly… at her funeral.”

“And where will you go now?””I shall go to Leipzig”

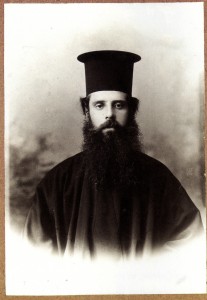

The man known to the world as Charilaos Philippidis, son of Zissis Philioglou, was born in Komotini (Gumulcina) in March of 1881. Komotini was then a rural area that is described in detail in the Metropolitan’s Autobiography, and together with his traumatic childhood experiences, provide evidence of his indissoluble bonds with his family and homeland. The premature death of his father (merchant of wheat and silk worm cocoons) and two of his siblings created a profound trauma, as well as a sense of responsibility in the tender soul of little Charilaos. His widowed mother undertook the upbringing of her three surviving children, with the help of her sole protectors and supporters, her brother Yangos Karabasis and above all her sister Lambrini Pegiou (Pegiaina) who “even though she was illiterate and had no knowledge of commerce, ran the business splendidly,” as Chrysanthos wrote. He never forgot that “when later I was to be admitted to the Theological School of Chalce, my aunt Pegiaina gave me five gold Turkish pounds as my starting out money.” After completing his general education in Komotini, he continued his studies in Constantinople, at the famous Theological School of Chalce (1897-1903) where he made a name for himself with his brilliant studies and ethos (“… I once again received distinction in all subjects for the seventh year, which was as arduous as the sixth.”)

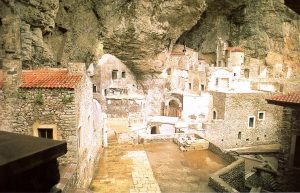

After his studies were over, and upon their commendation of the Metropolitan Ioachim Sgouros of Xanthi to Metropolitan Constantinos Karatzopoulos of Trebizond, Charilaos was ordained archdeacon at the Cathedral of Trebizond, at which time he took the name Chrysanthos. He was appointed teacher of religion at the city’s Frontisterio (school) and preacher. In 1904, at the age of just 23, he was assigned the duties of Genikos Epitropos (representative of the Metropolitan) of the diocese of Trebizond, seat of an important vilayet, and thereby undertook new responsibilities. His success in resolving the problems that arose in the relations between Christians and Muslims (forced conversions to Islam, groundless prosecutions of Greeks, etc.) as well as his undisputed administrative abilities, increased the prestige of the young Epitropos, who was totally dedicated to the increasing demands of the diocese. “I spent these holidays too in Constantinople, without being able to visit my homeland[…] I am once again very sorry, but duty comes before all.” The sudden death of his beloved mother in May of 1905 found him in Trebizond. “I lamented and mourned her death grievously, but at the same time I continued my work and on Sunday I preached in the church of St George Tsartakli about sorrow related to God and man.” The death of the Metropolitan of Trebizond two months later shook the city. Chrysanthos, who was already rundown through grief over the loss of his mother and wishing to avoid any involvement in the succession process, began a tour of the remote monasteries of Pontos: St John of Imera, Kromni, the Pariadros plateau (summer pastures), Livera, the Soumela Monastery and the Monastery of St George Peristereotas. Upon his return, Chrysanthos addressed the newly elected Metropolitan Constantinos Arampoglouon behalf of the community: “coming into this community you will find it flourishing and prosperous for all…”

Having become aware that he was expending all his creativity on his growing obligations (Exarch of the Monastery of Soumela, teacher at the Frontisterio of Trebizond, Epitropos of the Diocese), he decided at the end of the 1907 school year to resign from all his duties and devote himself to the purpose which attracted him and in which he had excelled: to continue his higher education in Western Europe, and in particular at Leipzig. The expenses of his stay there were borne by two friends from Trebizond who were pillars of the Greek community, Georgios Fostiropoulos and Constantinos Theophylaktos. The first stop was Vienna, where he attended classes in Philosophy by the famous professor Wundt, Canon Law by Zoom, and Linguisticsby Bruggeman. He met sociologist George Scleros (Georgios Konstantinidis) and made friends with poet and author Constantinos Hatzopoulos who dedicated two poems to him (“On a tree” and “On the same tree”), evidence of the close intellectual contact and friendship that linked the two men. Moreover, Chrysanthos kept up his relations with the intelligentsia. Athanasios Souliotis-Nikolaidis, D. Glinos, N. Politis, G.Hatzidakis, the famous English archaeologist William Boyd Dawkins, Stephanos and Ion Dragoumis, and Penelope Delta, who consulted him when she was writing the Life of Christ, were just a few of those in his immediate environment. His broadness of mind, profound culture and love of art were well known. We read in his Autobiography: “Throughout the school year, I took part in the rich artistic life of Leipzig, attending the entire series of Wagner’s works at the theatre, the then famous operettas of Vienna, productions of works by Schiller, Goethe and Ibsen, performed by first class theatre companies…”

During subsequent years, Chrysanthos continued his studies in Switzerland (Lausanne), where he was fortunate enough to attend courses in sociology given by Vilfredo Pareto and where also he chanced to meet musicologist Melpo Merlier, founder of the Centre for Asia Minor Studies in Athens (“Every Saturday I was in audience of rehearsals for the Sunday music programs. Classical works were performed that were introduced and performed by the Greek artist and Melpo Logothetti, later Merlier.”)

Return, Ekklesiastiki Alitheia, ascent to the Metropolitan throne

Chrysanthos returned to Constantinople in1911; he was immediately appointed Archivist at the Ecumenical Patriarchate and editor-in-chief of Ekklesiastiki Alitheia, the official journal of the Patriarchate. For the future metropolitan, this was the period of his initiation into issues of ecclesiastical order and tradition, giving him a more complete overview of Church problems. By publishing numerous papers in Ekklesiastiki Alkheia, he was given an opportunity, on the one hand, to put forward the political positions that reflected his own idealism, and on the other to make his presence felt on the intellectual level and as future leader. The following year, now an archimandrite, he was sent as Exarch to Venice to study the problems of the Orthodox community there. Chrysanthos submitted an enlightening memorandum recommending ways in which to save the community’s property, which the Italian government was planning to appropriate. The importance of this memorandum can be judged by the fact that it was used 35 years later in the ecumenical negotiations that followed the peace treaty ending World War II.

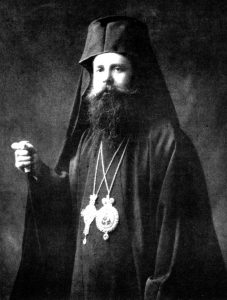

On 18 May 1913, the Ecumenical Patriarchate, in response to the common demands of clergy and laity alike, elected Chrysanthos as Metropolitan of Trebizond. The church in Trebizond, having known Chrysanthos as a young but gifted deacon, became familiar with him as a prelate and national leader who undertook the duties of both moral shepherd and animating spirit and fighter in the effort to ensure the spiritual and physical survival of the people of his second, adopted home.

On 18 May 1913, the Ecumenical Patriarchate, in response to the common demands of clergy and laity alike, elected Chrysanthos as Metropolitan of Trebizond. The church in Trebizond, having known Chrysanthos as a young but gifted deacon, became familiar with him as a prelate and national leader who undertook the duties of both moral shepherd and animating spirit and fighter in the effort to ensure the spiritual and physical survival of the people of his second, adopted home.

The decade of the Chrysanthos pastorate unfortunately coincided with the final phase in the almost two-thousand-year history of the Pontic Greeks. The repercussions of the declaration of World War I transformed the Trebizond area as well as the entire Pontos into a battlefield where hordes of Turkish irregulars gave themselves over to plunder, rapine and violence in all forms against the Greek population.The metropolitan, with the diplomatic insight and acumen that characterized him, believed that, in order to stop these attacks, the Turks would have to be convinced of the absolutely law-abiding nature of the Greeks. He achieved this by hastening in person to Cemal Azmi Bey, the prefect (vali) of the vilayet, as guarantor of the Greeks, and by giving instructions to the Greek leaders of the neighboring ecclesiastical provinces of Rhodopolis and Chaldia to do likewise. Due to his intercession, the deportation of three hundred Greeks (Russian citizens) to the depths of Mesopotamia under most adverse weather conditions was canceled, as was the departure of the notorious “labour battalions” (amele taburu) consisting of Greeks obliged to follow the army towards Diyarbakir and the Syrian frontier, where they were to work in heavy road-building projects until they dropped of exhaustion. Thus the Christians who had been conscripted into the labour battalions were not sent away from Trebizond, but did lighter tasks, while teachers, professors, chanters, sacristans and church wardens were exempted from the conscription. Chrysanthos provided a solution to another problem as well: the situation faced by the Greek communities in the Bulgarian-ruled Balkan provinces. While the negotiations Click to enlargefor an alliance between the Greek and Serb governments were going ahead, the metropolitan published a fiery article entitled “Blood and Fire” in Ekklesiastiki Alitheia on 1st June 1913, in which he launched a blistering attack against the Bulgarians because, on the basis of the Bucharest Conference, there was a danger that Western Thrace would be given to Bulgaria.

The arrival of the Russians. The leadership of the Prelate

In April 1916, the Russians were approaching Trebizond. The Turkish authorities withdrew, assigning Chrysanthos, as president of the temporary administration of Greeks and Turks, to maintain the order and safety of the population, Christians and Muslims alike.The Metropolitan agreed and addressed Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolayevich, using his power and authority to the benefit of all the inhabitants of Trebizond. Chrysanthos tried to retain control, although his efforts to save the Armenians had not been effective. The persecution and extermination of the Armenians (1915-16)had outraged a large number of Russian soldiers, many of whom were of Armenianorigin. The Russians assigned him to run the city, having full confidence in his administrative and diplomatic abilities, and discerning in his person a guarantee of the harmonious co-existence between Greeks and Turks. Without discriminating on grounds of race or religion, Chrysanthos extended his social action to the care of thousands of refugees (Christians, Muslims, Armenian orphans) guidin g the Charitable Brotherhood of Trebizond and securing financial assistance for the Pontians of Russia from the Russian government. As leader of the Pontic Greeks, his prestige increased when, in July of 1917, Grand Duke Nikolay, contemplating the repercussions of a prolonged Russo-Turkish war, asked him to approach the Turkish government and recommend that it make peace, an effort which unfortunately was not successful.

g the Charitable Brotherhood of Trebizond and securing financial assistance for the Pontians of Russia from the Russian government. As leader of the Pontic Greeks, his prestige increased when, in July of 1917, Grand Duke Nikolay, contemplating the repercussions of a prolonged Russo-Turkish war, asked him to approach the Turkish government and recommend that it make peace, an effort which unfortunately was not successful.

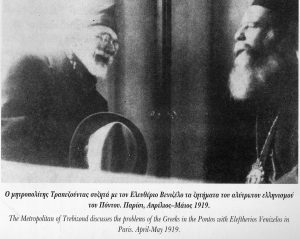

In 1918, the truce that ended World War I gave new hope to the Greeks of Pontos. They believed that the promises of the allies and the declaration of the US President Wilson about the self-determination of the peoples would be carried out. Early in 1919, Chrysanthos traveled to Paris as one of a three-member delegation consisting of the vicar of the Ecumenical Throne Metropolitan Dorotheos of Prusa, Alexandras Papas and himself. This mission represented the Greeks of Asia Minor at the peace conference.

In 1920, he traveled to Tbilisi in Georgia, working to re-establish the auto cephalous Orthodox Church there. From Tbilisi he went to Yerevan, capital of the newly constituted Armenian Republic, where he negotiated the creation of a Ponto – Armenian Federation. Upon his return, he not unnaturally faced the wrath of the Turks and sought refuge, for safety’s sake, in Constantinople, then under Allied occupation. On 20 September 1921, he was condemned to death in absentia by the Kemalist Independence Court, which after summary proceedings had already sent 69 Greek notables from Amisos and other regions to the gallows. In 1922, the Prelate was obliged to flee from Constantinople, as it had been abandoned by the Allies, and to establish himself in Athens, where in 1926 he was appointed accredited representative of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. His knowledge of ecclesiastical matters, his broad learning, his ethos and refusal to dabble in politics (“by nature and education I abstain from any involvement in petty politics…”) were appreciated by the Greek government, which entrusted him with a number of missions. Albania (1927), Belgrade, Bucharest, Warsaw (1929), Mount Athos (1929, 1920, 1935) and Cyprus (1931) were just a few of his successful efforts to settle matters arising in the Churches outside Greece.

From 1928 until his death in 1949, Chrysanthos served as chairman of the Committee of Pontic Studies, and was a founding member of the internationally acclaimed scholarly journal Archeion Pontou (1928), which is still being published to this day.

In December of 1938, he was elected Archbishop of Athens and All Greece. During his brief pastorate as archbishop, he had an opportunity to demonstrate the full range of his administrative abilities and the virtues of a true religious leader. When the Click to enlargeItalians attacked Greece, causing a multitude of young Greek soldiers to be sent to the mountains of Albania, he reacted as though he were still metropolitan of Trebizond, entrusted with the sacred duty of saving or at least relieving his flock. He organized “Welfare of Enlisted Men”, collected and sent significant financial help to the families of enlisted men; he visited the wounded, and sent packages to the front. A flurry of events followed. Anthimos A. Papadopoulos reports:

On the ill-starred day of 27 April 1941, the vanguard of the Germans arrived in Ambelokipi [district of Athens]. As early as the 24th of the month [Chrysanthos]had been called to serve as chairman of a committee that would hand the city officially over to the Germans. But the Prelate refused saying: “The Archbishop does not agree to take part in the committee to surrender the city to the enemy, the work of the Archbishop is not to submit, but to liberate.” How could this prelate whose enthronement speech as metropolitan of Trebizond had proclaimed: “I prefer flying as an eagle to fall, rather than crawling, to live” – have done otherwise?

At the Diocese Synod, he stood up to receive General von Stummer, commander of the second army corps, whom he asked directly why Germany declared war on Greece. And of course, he refused to swear in the collaborationist government: “What kind of government are you? Constitutional? No, because you do not have the mandate of the king. Revolutionary? But you are not that either… You are a government imposed by foreign invaders…”

Chrysanthos was dismissed from his post on 2 July 1941 and withdrew to a little house in the Kypseli district of Athens, which upon his request, was renamed Soumela St. Throughout the German occupation he did not take a single step outside this house. Penniless, he was sustained by the generosity of his friends. It would be a grave omission to overlook his election on 28 November 1939 as a member of the Academy of Athens. The enormous volume of his writings, including articles in Ekklesiastiki Alitheia, the periodical Komninitis Trapezountos and other publications, his edition of two speeches by Bessarion from the National Marcian Library in Venice, but primarily his monumental 900-page work about the Church of Trebizond that was published as a series in Archeion Pontou by the Committee of Pontic Studies, indicate the magnitude of his intellectual contribution. He was awarded an honor arydoctorate by the University of Athens School of Theology for his learning and exceptional ethos. The speech he made on the subject “The Church and culture in our East” at his official reception by the Academy of Athens on10 February 1940 was his first paper as an Academician. It was a significant study that captured the Prelate’s breadth of spirit in accepting both the role of the ancient Greek tradition and of the Church in “our East”. “Orthodox Greek Christianity absorbs everything the East has in terms of passion, strength and enthusiasm; the Church, under the influence of the Hellenic spirit, tames and embellishes and distinguishes the unformed depth of soul and life and art of the peoples of the East in the ethereal pure and merry lines and forms of the Greek soul and life and art…”

After the German occupation had ended, the prelate did not seek to return to the archbishop’s throne, so as not to create internal irregularities and discord. Besides, the attitude of state and Church alike, from the period of his withdrawal up to his death, was completely indifferent. Just a month before his death, on 28 September 1949, the Holy Synod recognized Chrysanthos as the former Archbishop of Athens (“with ecclesiastical frugality”) in order to offer him some rudimentary financial support. His desire to “have the plain unofficial funeral of someone who was just an ordinary priest” had been expressed orally to Georgios N. Tasoudis. But his last wishes were not observed, on the grounds that “Chrysanthos did not belong to his family, but to the Click to enlargeNation and the Church”. Thus he was given an official funeral with the honors of an archbishop, awarded the Grand Cross medal. An irony of fate? The rendering – albeit at the last possible moment – of justice? Whatever we may hypothesize, the fact is that it would have been inappropriate to respect the last wishes of a man who had offered his entire life to fulfilling his obligations to his congregation, to his country, to the idea of Freedom, and to the reconciliation of peoples. When his will, in which he disposed of his few possessions, was opened, the following codicil was also read:

After the German occupation had ended, the prelate did not seek to return to the archbishop’s throne, so as not to create internal irregularities and discord. Besides, the attitude of state and Church alike, from the period of his withdrawal up to his death, was completely indifferent. Just a month before his death, on 28 September 1949, the Holy Synod recognized Chrysanthos as the former Archbishop of Athens (“with ecclesiastical frugality”) in order to offer him some rudimentary financial support. His desire to “have the plain unofficial funeral of someone who was just an ordinary priest” had been expressed orally to Georgios N. Tasoudis. But his last wishes were not observed, on the grounds that “Chrysanthos did not belong to his family, but to the Click to enlargeNation and the Church”. Thus he was given an official funeral with the honors of an archbishop, awarded the Grand Cross medal. An irony of fate? The rendering – albeit at the last possible moment – of justice? Whatever we may hypothesize, the fact is that it would have been inappropriate to respect the last wishes of a man who had offered his entire life to fulfilling his obligations to his congregation, to his country, to the idea of Freedom, and to the reconciliation of peoples. When his will, in which he disposed of his few possessions, was opened, the following codicil was also read:

“When the Lord is pleased to call me from here, I ask that my funeral be held in a closed circle and with just one priest […].I request that this wish be applied faithfully and accurately. In Athens, 25 November 1941. Chrysanthos of Athens”